Evaluation

Day

By Michael Cunningham

Random Home: 288 pages, $28

In the event you purchase books linked on our website, The Instances might earn a fee from Bookshop.org, whose charges assist impartial bookstores.

Michael Cunningham is possessed by a spirit, one whom a great deal of modern writers discover it exhausting to shake: Virginia Woolf walks the hallways of his novels. Her motifs pop their heads in, his characters share names with hers, and his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1998 novel “The Hours” revives Woolf herself as a protagonist.

In fact, Woolf stands as a foundational pillar for modern literature, and her affect is aware of no bounds. (In her new novel “My Work,” Danish creator Olga Ravn relays “the impression that any artwork made by a girl besides Virginia Woolf was a secret.”) However in “Day,” his first new novel in 10 years, Cunningham resurrects the long-dead English novelist within the unlikely type of an aspiring Instagram influencer referred to as Wolfe, who’s the truth is the fictional creation of depressed 30-something Brooklyner named Robbie. Virginia Woolf, GRWM?

Like “The Hours,” this novel is split into three acts. “Day” takes place on the morning of April 5, 2019; the afternoon of April 5, 2020; and the night of April 5, 2021. Pre-pandemic, early pandemic, later pandemic. Though COVID-19 is rarely talked about by title, Cunningham pressed his level in an interview earlier this 12 months. “How does anyone,” he requested, “write a recent novel that’s about human beings that’s not in regards to the pandemic?”

However with new emergencies speeding by us every day, I discover it tougher and tougher to abide literature involved with the pandemic itself, relatively than its long-tail outcomes. (Woolf’s personal “Mrs. Dalloway” — an apparent affect on “Day” — benefited from being set after, not throughout, the flu epidemic of 1919-20.)

And but, “Day” isn’t actually in regards to the pandemic in any respect, and its first part, set lengthy earlier than anybody in addition to virologists had ever uttered the phrase “coronavirus,” is by far its strongest. Cunningham scatters his characters to their separate emotional exiles with an intention to deliver them collectively at day’s (and ”Day‘s”) finish. Dispersal is his forte.

Robbie and Isabel Walker are a brother and sister dwelling on the cusp of nice change. Robbie deferred medical college a decade earlier and teaches sixth grade, dwelling within the leaky attic room above the “starter residence” Isabel and her household have occupied far longer than anticipated. Robbie is, ostensibly, planning to maneuver out so Isabel’s preteen son can have a room of his personal; his residence search is the standard dismal and humbling New York expertise, and each siblings waver on whether or not he ought to go.

In the meantime, Isabel wonders how lengthy she will march towards irrelevance as {a magazine} editor; her husband, Dan, a former C-list rocker who “regarded, at age twenty, like a seraph out of Botticelli,” now cooks up pancakes for the children relatively than hit songs; and their 5-year-old daughter Violet “is coming right into a world of hidden guidelines, which she will be taught solely by breaking them.”

I all the time hate these types of plot summaries in evaluations — a bunch of characters caught up in trivial-sounding trivialities: Who cares? However Cunningham superbly pries aside the notion of what it means to have outgrown one thing, to be dwelling within the liminal area between an earlier self and a future self, to be unable “to reenter the orderly passage of time.” “Day” is even set on a date New Yorkers will acknowledge as a sort of fake spring, when, in defiance of the calendar, the earth stays exhausting and the flowers huddle underground.

Cunningham’s huge mission has all the time revolved round inspecting time’s fitfulness. Like Henry James in “What Maisie Knew” — the 1897 divorce novella written from the standpoint of the kid — Cunningham understands that the tipping factors of childhood are ripe moments for examination. As Violet ages — from 5 to six to 7 in a single protracted day — she begins to tackle an inside life her mother and father can’t entry and even see. She’s conscious that she is rising up and that doing so requires a sort of manufactured innocence placed on for her mother and father’ sake. “At what age do youngsters start to understand,” Cunningham asks, “that they’re anticipated, generally, to be parodies of youngsters?”

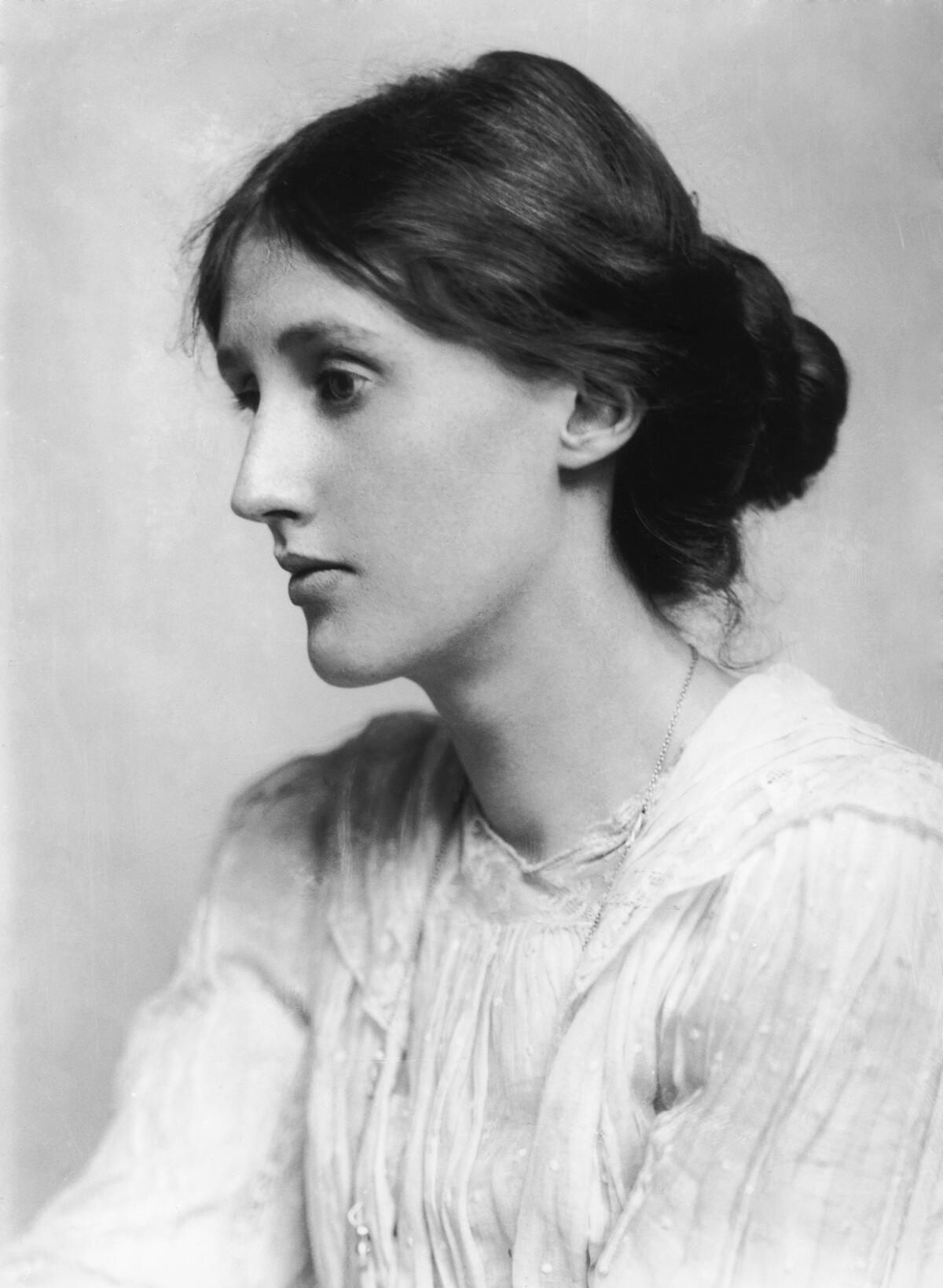

Virginia Woolf was a core topic of Cunningham’s “The Hours.” She pops up once more as an affect on his new novel, “Day.”

(George C. Beresford / Getty Photos)

The comparability to James would in all probability really feel apt for Cunningham. He’s all the time in dialog together with his forebears and contemporaries, aware that literature is a huge internet and his personal work has an extended ancestry and dwelling kinfolk.

In “Day,” two characters take a street journey to go to “the world’s second-largest ball of twine,” an inane, ironic vacationer spot that closely hints at “essentially the most photographed barn in America” in Don DeLillo’s “White Noise.” There are different nods to George Eliot, Colm Toíbín, Shakespeare’s tragedies. One character teaches college literature, and as her class discusses Edith Wharton’s “The Home of Mirth,” she reminds everybody that the 1905 novel is “kind of the tip of the wedding story.” Then she asks in the event that they’ve “learn the Vivian Gornick,” which means the critic’s essay “The Finish of the Novel of Love,” which demoted the love story from its central place in literature.

However on this novel that puzzles over the elasticity of every kind of affection — familial, parental, erotic, queer, fraternal, ambiguous — I yearned for Cunningham to neglect his literary friends and stick together with his personal particular expertise for proving Gornick unsuitable. Sure, the normal “marriage story” not works, however Cunningham is a author who understands the flexibleness and freedom that comes after that sort of narrative collapse.

Till its finish, when the novel loses its approach by killing off a personality (Woolf’s calculation: “somebody should die so that others worth life extra”), “Day” is at its contemplative finest when it shakes off affect and oversight. Robbie and Isabel, siblings who love one another the best way a drowning man loves his life jacket, are not any “small good factor,” as Gornick may need referred to as them. They’re the largest factor, the one factor. And when Cunningham writes like himself, and never like an apostle, he’s certainly one of love’s best witnesses.

Kelly’s work has been revealed in New York Journal, Vogue, the New York Instances and elsewhere.

#Evaluation #Michael #Cunninghams #timebending #COVID #Day