The very first thing you discover in regards to the work of Tidawhitney Lek is the arms. Fingers slink round doorways and sofas and emerge out of closets and gutters. They play with the locks in your door if you are napping and cleaver banana vegetation in the midst of the night time. Typically the arms are inexperienced; different instances, human shades of brown. All the time, they bear glittery manicures. By no means is it revealed to whom these arms would possibly belong or whether or not their intention is protecting or sinister.

“Folks all the time ask me, ‘Pal or foe?’” Lek says of the mysterious appendages. “I say, ‘That’s the concept.’”

The magic in Lek’s work extends effectively past arms. On the floor, her work seem to chronicle intimate home scenes. In a single canvas, a girl dozes peacefully on a sofa; in one other, two ladies linger in a lush backyard. However look nearer and also you’ll discover particulars that unsettle. The sleeping determine rests on a settee whose abstracted sample evokes a swarm of winged bugs. And the backyard the place the ladies idle isn’t a single house however a vertiginous composite of a number of areas whose angles defy the legal guidelines of physics.

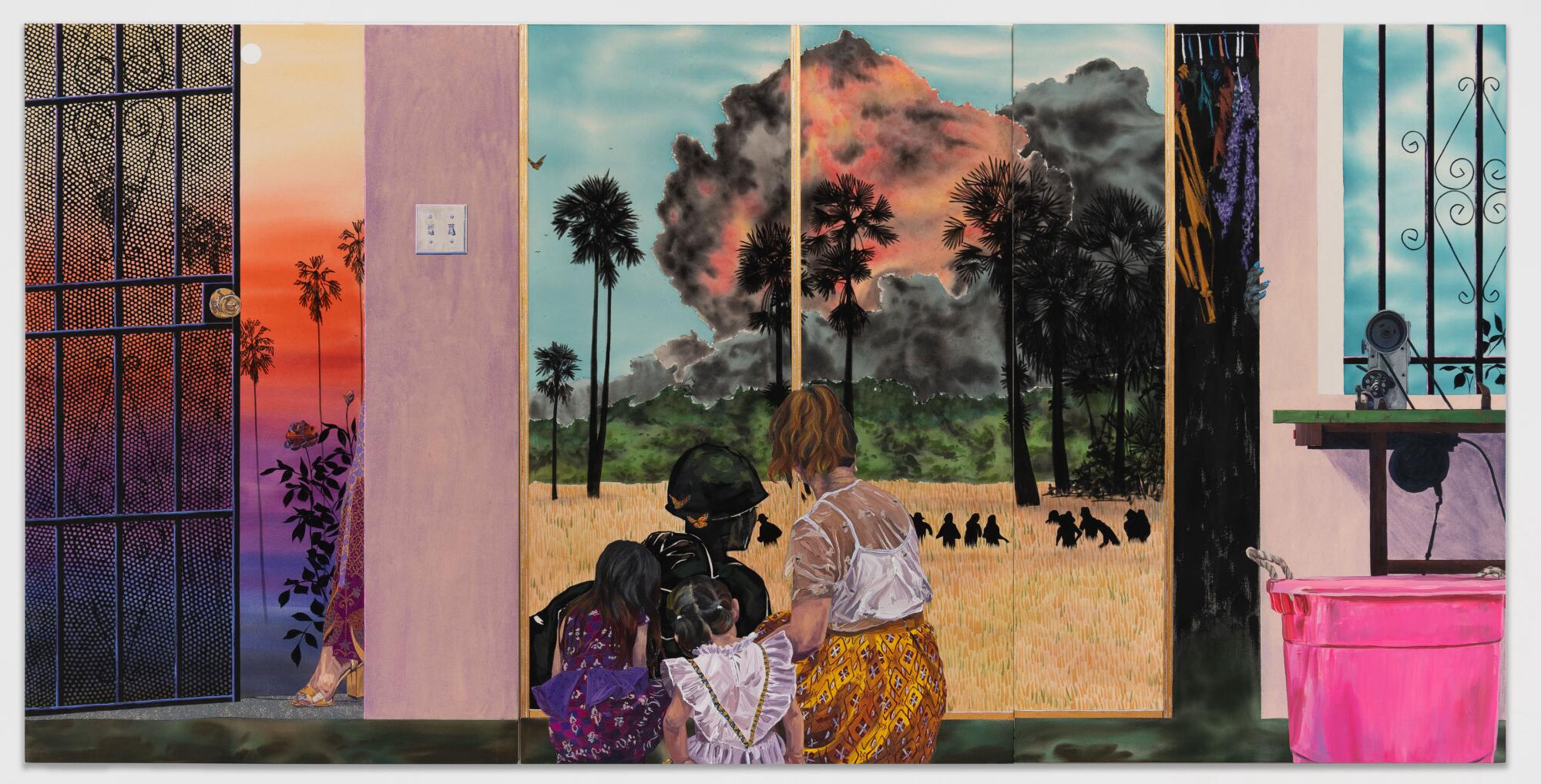

No work of Lek’s, nonetheless, disorients fairly like “Refuge,” a three-panel portray accomplished in 2023 that extends to a width of 12 ft. Now on view in “Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Residing,” the sixth iteration of the Hammer Museum’s biennial, it reveals three ladies, seen from behind, reacting to the bombardment of the Cambodian countryside within the Nineteen Seventies. Give the canvas a fleeting look and it might sound as if the ladies are huddled behind a soldier in a rice paddy.

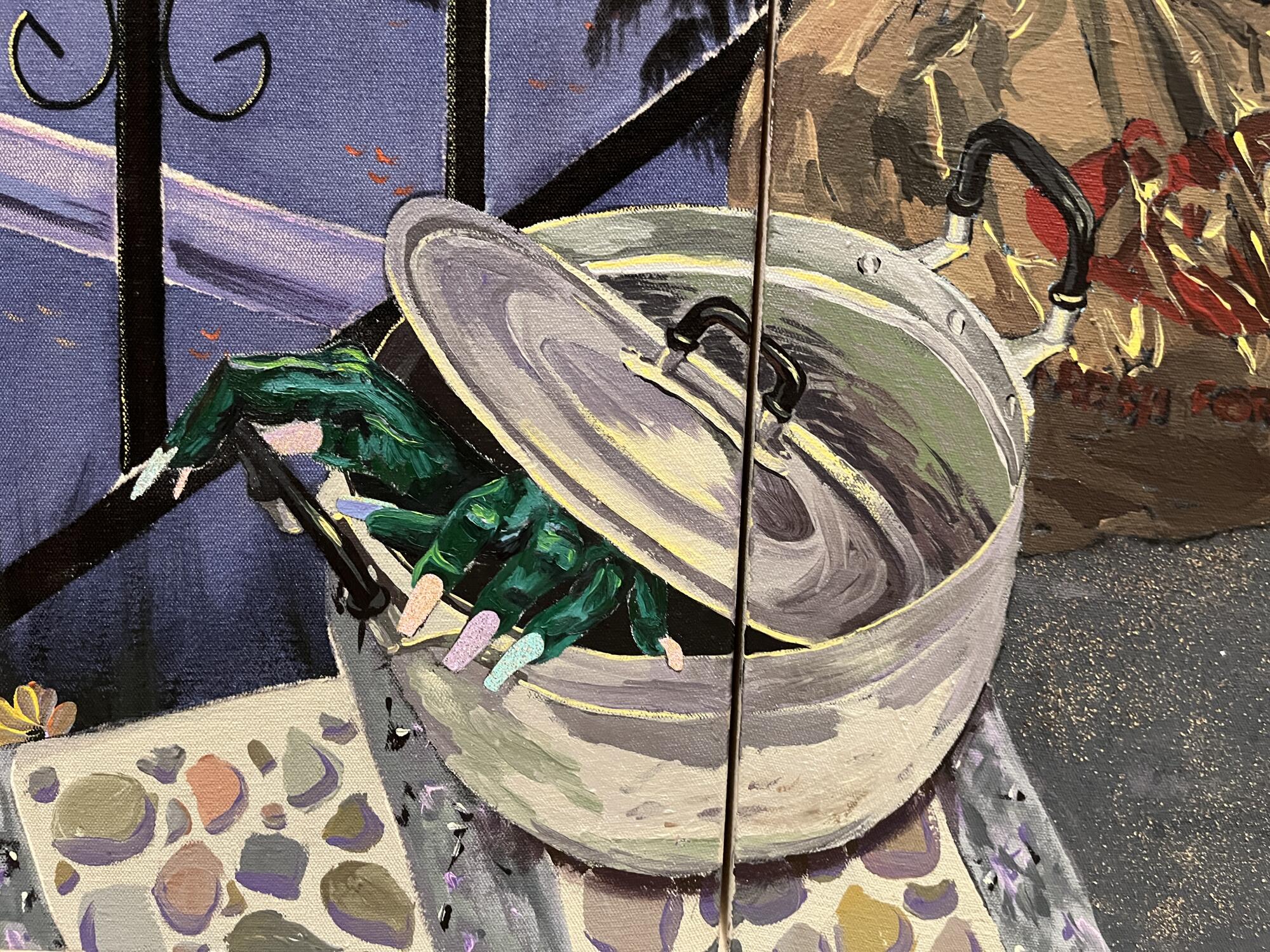

However look once more and also you’ll discover that this wartime scene — impressed by the experiences of Lek’s Cambodian father — is one thing else fully. The explosion is definitely rendered on the floor of a closet door in a secular condominium the place the ladies sit subsequent to a pink bucket and a stitching machine. Naturally, there’s a hand: a gnarled, inexperienced claw that emerges from the depths of the closet, like a ghost of the previous reaching into the current.

In Lek’s work, wealthy colours catch the attention: sunsets in shades of Los Angeles poisonous and many glowing sampot — the normal Cambodian wrap worn across the decrease physique. However horrors actual and cinematic simmer simply beneath the floor. Diana Nawi, an impartial curator who served as co-curator for “Acts of Residing,” says Lek’s work incorporates humor, “however additionally it is tied to this very actual violence.”

Tidawhitney Lek’s “Refuge,” 2023, is on the Hammer Museum’s biennial, “Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Residing.”

(Tidawhitney Lek / Sow & Taylor)

On a heat Monday morning in October, Lek greets me and Instances photographer Genaro Molina with strawberries and freshly brewed tea in her sunny studio, positioned above a scrum of stalls promoting succulents and bamboo within the Flower District. Hanging on partitions and propped up in opposition to columns are a collection of latest work that may seem in “Residing Areas,” a solo present that opens Friday on the Lengthy Seaside Museum of Artwork’s satellite tv for pc exhibition house within the metropolis’s downtown. In a single canvas, a hand with glowing pink nails grips a door body in a setting that confuses indoors and out; in one other, a gaggle of males in Western gown play a Cambodian cube recreation referred to as klah klok.

For Lek, this can be a second of institutional prominence. Her work open the Hammer biennial simply as she is about to have her first museum solo. However her success follows a interval of looking out — trying to find the suitable visible language to articulate her expertise because the U.S.-born daughter of Cambodian refugees who survived the horrors of the Khmer Rouge’s genocidal regime within the Nineteen Seventies.

“These work are my diaries,” says Lek. “I’m actually in dialog with myself. What was yesterday? What’s in the present day? And what’s going on tomorrow?”

Lek, 30, was born and raised in Lengthy Seaside to folks who emigrated from Battambang, in northwestern Cambodia. “I’m the primary technology of an immigrant household that grew up actually poor on Part 8,” she says. “My mother has six children. I’m quantity six.”

In Cambodia, her paternal grandfather had been a tailor. On her mom’s facet, her grandfather had labored as some kind of service provider. “My mother doesn’t say an excessive amount of about her previous,” Lek says. “However she has mentioned her father was a businessman. He bought and traded.”

Lek’s dad or mum’s have been adolescents when the totalitarian Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia in 1975, emptying out cities and systematically killing the nation’s skilled and mental courses. Almost 1 / 4 of the inhabitants (about 1.7 million individuals) died throughout its rule from violence, overwork and hunger. Her mother and father survived, however many prolonged members of the family didn’t.

Tidawhitney Lek is surrounded by her work in her Flower District studio.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Instances)

After the Khmer Rouge fell in 1979, the couple made their method to refugee camps in Thailand and the Philippines. By 1984, they’d relocated to the US, residing for a short while in Boston earlier than settling in Lengthy Seaside, dwelling to a big Cambodian diaspora clustered on the jap facet of the town in a neighborhood often known as Cambodia City.

Cambodia’s historical past stretches again centuries and contains magnificent traditions in temple structure and bronze sculpture. However the Khmer Rouge’s four-year reign of terror casts an extended — and sometimes silent — shadow. “For college, we’d have these assignments the place it’s like, ‘Go ask your mother and father what it was like after they have been rising up,’” remembers Lek. “They usually’d be like, ‘Why do it is advisable do that?’”

Artwork was vital to Lek from an early age. “Since I used to be a child, I used to be the artwork woman,” she says. “However my mother and father all the time advised me that this was one thing that was not going to pay the payments.”

After she enrolled at Cal State Lengthy Seaside within the early 2010s, Lek left her main undeclared, figuring she’d pursue artwork whereas making ready to turn out to be a math trainer. However a go to to New York Metropolis in 2014 upended that plan. That 12 months, she joined a pupil journey led by painter and Cal State Lengthy Seaside professor Tom Krumpak that included visits to a mess of artist studios. Rising up in Lengthy Seaside, she says, “I had by no means actually been uncovered to the up to date artwork scene right here.” However the journey pulled again the curtain on that world. “New York,” she says, “turned one thing in me.”

Lek didn’t begin out by portray her household. At school, she favored abstraction: “Brush marks, gradients, working with the feel of paint.” However she wasn’t certain how real it felt. She remembers certainly one of her professors, painter Siobhan McClure, asking her: “Tida, why don’t you paint who you might be?” However Lek says she wasn’t able to reckon with that. “That was a time once I was nonetheless sad with the place I come from and I used to be nonetheless digesting what it meant to personal that.”

However after she graduated in 2017, the artist started to come back round to figurative work. Within the months after commencement, she spent formative stints working within the studios of some Los Angeles painters, together with Annie Lapin, Amir H. Fallah and Danielle Dean, which acquired her considering deeply about shade and juxtaposition of photos. And he or she was seduced by Kerry James Marshall’s solo present on the Museum of Up to date Artwork Los Angeles in 2017. “I noticed his retrospective at MOCA like thrice,” she says. “I used to be like, ‘That is improbable. I’m seeing this individual on this entire group of work and the way he manifests what’s round him.’”

“Kinfolk,” 2022, on view on the Hammer Museum.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Instances)

A element of “Kinfolk” bears a signature Lek picture: disembodied arms.

(Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Instances)

She started by portray interiors. “I made a decision that my dwelling was the very best place to begin,” she says, considering of rooms as “levels” the place a narrative may very well be implied. She then turned to her household. A key work, “Slicing Threads,” from 2020, evokes the surreal nature of so most of the work which have come since: a pair of arms emerge from a tv set and join, by way of a tangled purple thread, to a different pair of arms working a stitching machine. The scene was impressed by her mom. “She loves watching TV whereas she sews,” says Lek. “That’s why I put these issues collectively.”

The method of partaking her household led to conversations about their historical past. Her father, she realized, wrote an autobiography in Khmer and as soon as slipped a duplicate of it onto the cabinets of a neighborhood library. Now, he reads to her from it occasionally (a sluggish course of, since Lek isn’t very fluent in Khmer). The bombardment proven in “Refuge” was impressed by an anecdote from the e book, through which her father makes an attempt to find his household in the midst of crossfire in the course of the fall of the Khmer Rouge.

“After I began portray my household in my dwelling, it was actually tackling issues I’d been wanting to speak to them about,” says Lek. “It’s not till we make the work that we discover room to deal with it.”

Lek arrived at her singular model at a fortuitous second. Final 12 months, a solo present of her work at Sow & Taylor in Historic South Central caught the attention of the curators for the Hammer’s biennial. Pablo José Ramírez, a workers curator on the museum who organized the biennial with Nawi, says Lek’s work have been among the many first works they noticed as they started the curatorial course of. He says a part of the hazard of seeing a piece early is that it might slip from reminiscence when it comes time to resolve on the checklist of taking part artists. However Lek’s work stayed with them.

“There’s something worldwide with portray going again to surrealism now,” he says. “The final Venice Biennale had a giant part on surrealism. However that is the primary time I’ve seen one thing like Tida’s work.”

Nawi says Lek’s disconcerting juxtapositions drive the viewer to ask, “The place are we and when are we?”

Lek says her success has reassured her household that she made the suitable skilled selection. Although her older brother, in typical sibling trend, was unimpressed when she advised them that she was going to seem in “Made in L.A.” “He was like, ‘Hammer Schmammer, I don’t know what that’s,’” she says with amusing.

In the end, what motivates her isn’t the institutional approval however the encouragement she receives from fellow Cambodian Individuals, who discover their truths on her canvases. “I’ve my neighborhood attain out to me by way of Instagram, or family and friends who I hadn’t heard from,” she says. “They’re like, ‘Yo, I noticed your work. Hold telling our story.’”

‘Made in L.A. 2023: Acts of Residing’

The place: Hammer Museum, 10899 Wilshire Blvd., Westwood

When: Via Dec. 31

Information: hammer.ucla.edu

‘Tidawhitney Lek: Residing Areas’

The place: Lengthy Seaside Museum of Artwork, LBMA Downtown, 356 E. third St., Lengthy Seaside

When: Via Feb. 4

Information: lbma.org/lbmadowntown

#Tidawhitney #Leks #Lengthy #Seaside #solo #present #paints #Cambodian #lives